![Pathé PAT 36 [CPTX 165] label Pathé PAT 36 [CPTX 165] label](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjFBdRRLcqs2jpwUEtKppy47MGTWuIUVhysun61snO1KwTrm23robe86dz3Jf2A0l_sHx66ofBYzI7a0c24E1gzEizJ4cxDyqnHM35_MgMM6TDzQjA5y2SQ09AJz2A0iFaHcABfnJ88aNPv/?imgmax=800)

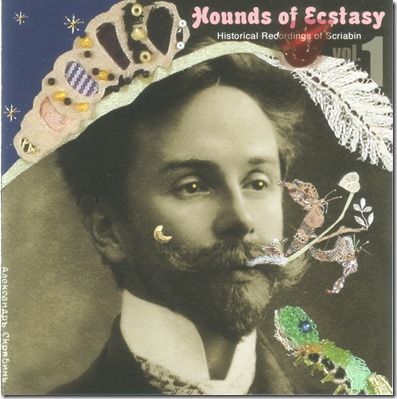

Pathé PAT 36

Pierre Danican Philidor (1681-1731)

Suite for treble instrument & continuo in e Op.1 No.5

Pathé PAT 37

(also issued in Japan on Columbia J 8584)

George Frideric Handel

Sonata for flute & continuo in b Op.1 No.9 HWV 367b

[NB penultimate Andante omitted]

Jean/Jan Merry (flute)

Pauline Aubert (harpsichord)

rec. 13 June 1935

(date: A Classical Discography)

And I thought this was going to be ‘easy’. Spurred on by bloggers like Jolyon, not to mention eminent historians of concert culture such as Dr. Christina Bashford, I now feel my posts should include more information about artists, especially obscure ones. In the immortal phrase of one Jezza, ‘How difficult can it be?’ Little did I know that it would take me well over a year just to find Jean Merry’s dates…

Naturally, I started with Susan Nelson. Her great discography The Flute on Record: The 78 rpm Era gives Merry’s birth date, but no place of birth or date of death. Then followed months of sporadic online searches, visits to libraries, e-mails to flautists, historians and conservatoires: nothing. Until, a few weeks ago, searching digital repositories at the British Library, I came across a thesis entitled A Performance Edition of Charles Kœchlin’s Les Chants de Nectaire, Opus 198, which put me out of my misery:

1897-1983

Many thanks to the author, Dr. Francesca Arnone, flautist and teacher, who has also sent very friendly answers to my e-mails. In her thesis, submitted in 2000 to the University of Miami, Dr. Arnone warned that ‘much information about Merry cannot be recovered’. There’s now far more about him out there – though still not his dates, let alone an obituary. Still, from Gallica, Ancestry.com, academic and other sources, including Dr. Arnone’s thesis, I’ve been able to piece together a fair picture of Merry’s life and work. I’ll concentrate on the ’20s to the ’40s, the decades most relevant to these discs and also the best documented in accessible sources. It has taken me so long, I’m jolly well going to give you the lot! Sorry if it’s tedious, but that’s who I’ve become: not just a grump but a bore.

(And apologies if I appear to neglect Pauline Aubert (1884-1979); she also deserves study – as far as I know, there’s no website or page devoted to her, let alone a printed biography – but she’s better known than Merry, and she recorded much more.)

First, the flautist’s name: on the label of PAT 36, he is billed as Jean Merry, and on that of PAT 36 as Jan Merry. He seems to have used the latter as a stage name. As Nelson states, he was in fact born Jean Merry-Cohu; Cohu is a Normand name, and Nelson adds that Merry studied at the Conservatoire of Caen – where, I’m guessing, he was born. The Conservatoire was one of several institutions and people I contacted about Merry, in May 2016, and it had the grace to answer: no documentation survives from before Wold War II. Caen, the archivist reminded me, suffered very badly from Allied bombing raids in 1945.

In 1923, the newspaper L’Ouest-Éclair, listing forthcoming ‘musical masses’ at the cathedral of Saint Malo in Brittany, named one performer as ‘Merry Cohu, 1er prix du Conservatoire de Caen’, a distinction I haven’t seen documented elsewhere. In 1999, Dr. Arnone was able to interview a member of his family for her thesis:

At the age of ten, Jan Merry was offered free lessons in Normandie by the flute professor at the conservatory who considered the boy to have natural talent. Since his widowed mother could not afford an instrument, he was given the school’s flute to use.

Who that kind teacher was, I don’t yet know (ten years after Merry attended the Caen Conservatoire, its flute professor was one Monsieur Brun; I don’t have the start date of his tenure). Merry’s mother, meanwhile, was named as his next-of-kin on the passenger list of the S.S. De Grasse, sailing for the USA from Le Havre on 23 September 1924:

COHU Merry 26 M[ale] S[ingle] [Occupation:] Civil Engineer [Nearest relative:] Mrs. Cohu 3, Rue du Pont St-Jacques CAEN (Calvados) [Final Destination:] Ohio Cleveland

‘Civil Engineer’? I’ll come back to that. Did Merry go to Cleveland for professional reasons? I don’t know, but he apparently played with the Cleveland Insitute of Music orchestra; back in France, he was once billed as ‘soliste de l’orchestre du Conservatoire de Cleveland’. The CIM did not respond to an e-mail enquiring about him, and I’ve found no mentions of him in US newspapers. Once more, Dr. Arnone to the rescue:

Merry began his professional musical career by concertizing in the United States with his first wife, an American pianist. After living in New England for a time, they returned to Paris […]

Merry’s first wife was Eleanor Stewart Foster (1897-1986), sister-in-law of the composer Roger Sessions. According to Andrea Olmstead’s biography of the composer, they were married in 1927, in Paris:

Sessions gave the bride away. He also gave Merry a solo flute piece, Pastorale, perhaps a wedding present; the piece is now lost.

In France, Merry continued his musical partnership with his wife, usually styled ‘Elen Merry’ in the French press, less commonly ‘Ellen Merry’. In February 1928, they gave a concert in Paris, performing duos by Loeillet, probably Jean-Baptiste (1680-1730), Bach, Albert Roussel and Philippe Gaubert; she also played solos by Brahms, Darius Milhaud, Emmanuel Chabrier and Chopin, and he played Debussy’s Syrinx. Another Paris concert, in January 1929, included duos by Louis Couperin, Benedetto Marcello and Handel, Pierre Hermant (1869-1928), Joseph Jongen, Quincy Porter, and Lili Boulanger. The same month, Jan Merry took part in a concert entirely devoted to works by Georges Hüe (1858-1948), and in July he played in a ‘Festival Albert Roussel’, with the composer at the piano for his Joueurs de flûte Op.27. In December, the Merrys joined forces for a programme juxtaposing old French organ music with works by Georges Migot (1891-1976); they would collaborate with Migot again.

About this time, the couple also formed a trio, Ars Nova, with the French violinist Colette Franz (1903-2004), later a well-known teacher and founder of the first conservatoire in the French West Indies. Ars Nova made its debut on 17 December 1929, at a concert promoted by the Société Internationale des Amis de la Musique Française; the repertoire, which included vocal and piano solos, ranged from Jacques-Christophe Naudot, Joseph Bodin de Boismortier, Rameau and Couperin (probably François), to Fauré, Debussy, Roussel, Maurice Emmanuel (1862-1938), Pierre de Bréville (1861-1949), Lili Boulanger and Joseph Canteloube. The Trio received an ecstatic review from Georges Migot:

Il est excessivement rare d’entendre un ensemble de tels artistes. Chacun est virtuose et musicien, chacun peut établir seul, sa notoriété, chacun est digne de toute notre attention. Mais ces trois interprètes de race aiment assez la musique pour la servir en unissant leur triple personnalité. […] Quant à Jan Merry, je crois que, rarement, il a été donné de réaliser une telle alliance de la technique et des lèvres, car sa sonorité est à la fois distinguée et chaude, pure et variée sans cesse. […] On pressent un musicien cultivé, qui sait analyser la morphologie d’une œuvre, et mettre chaque détail bien en place. Nous le répétons; la sonorité de Jan Merry ne peut s’oublier après audition. Elle est rare. Et nous osons dire qu’elle est une des plus belles parmi celles que nous connaissons en Europe.

[‘It is exceedingly rare to hear an ensemble of such artists. Each is a virtuoso and a musician, each could win fame alone, each deserves our full attention. But these three thorough-bred performers love music enough to serve her by uniting their threefold individuality. […] As for Jan Merry, rarely, I feel, has it been possible for such a marriage of technique and embouchure to be achieved; his sound is at once elegant and warm, pure and ever varied. […] One is aware of an educated musician, able to analyse a work’s structure and place each element perfectly. Let me say again: once heard, Jan Merry’s sound cannot be forgotten. It is a rare thing. And we make so bold as to claim it as one of the most beautiful we know of in Europe.’]

Ars Nova did not last. A month later, on 21 January 1930, a second concert followed, with works by Bach, Handel, Boismortier, Couperin, Roussel and Petros Petridis (1892-1977), as well as the premiere of Migot’s Livre des danceries for flute, violin and piano (later orchestrated), and some of his Petits préludes for two flutes (or, as here, flute and violin). Besides a brace of broadcasts, Ars Nova gave two more concerts: on 14 November 1930, of works by Purcell, Couperin, Naudot, Boismortier, Ladislas Rohozinski (1886-1938), Carl Reinecke, Georges Enesco and Alexander Tcherepnin; and on 21 March 1931, devoted entirely to music by Migot. Although billed, Frantz was apparently not available that evening and was replaced by the Swiss violinist Magda Lavanchy (1901-76).

I suspect marital problems. After that last concert, I can find no more listings or mentions of Elen/Ellen Merry on Gallica. By March 1932, she reappears as Elen (or Helen) Foster; many years later, she related that, after divorcing Merry, she was obliged to revert to her maiden name. Still, the two continued to appear together in concert – of which, more below.

Also on the bill of that March 1931 Migot concert was the harpist Françoise Kempf (1901-1996). A few days earlier, on 16 March, Kempf and Merry had given the first of what would be many concerts and broadcasts together, as a duo and with other artists. I’ve found at least ten collaborations, from early 1931 until mid-1941, well after Kempf had reportedly undergone her mystical religious conversion in 1937.

Meanwhile, on 22 January 1932, Merry’s other important musical partnership was apparently inaugurated, in his first documented concert with Pauline Aubert. They played works by Frescobaldi, Couperin, Rulman (not identified), Duval (presumably François) and Rameau. After a gap, they appeared together in October or November 1934 (listings vary), in the salon d’Hercule of the palace of Versailles. Dressed in period costume, they were joined by string players in one of François Couperin’s Concerts royaux; the Russian emigré Sacha Votichenko (1888-1971) played an original tympanon, a type of hammered dulcimer popular in Marie Antoinette’s heyday; and Antoinette Bécheau La Fonta (1898-1971) sang ariettes galantes of the ancien régime. It was Mme La Fonta who organized this and other historical concerts in ‘authentic’ (my word) settings. In December 1932, she put on a second concert at Versailles, at which Merry and colleagues played Mozart’s Flute Quartet in A K.298, and works by Jean-Marie Leclair, Couperin, Giovanni Battista Somis and (Pierre de?) Chauvigny (?-?).

Pauline Aubert was not only a concert artist but also an editor and composer. She unearthed forgotten works, such as a cantata entitled Jupiter et Europe and attributed to one A. Pasquier (not identified). She and Merry performed it in late 1934, at a concert of the women’s orchestra conducted by Jane Evrard (1893-1984), alongside a flute concerto by Michel Blavet. In March 1935, Parisian concert-goers heard Aubert’s Poèmes persans, for voice and flute, performed by Merry and the soprano Madeleine Chardon. In April, Aubert and Merry gave a broadcast talk, with music, on ‘Les Couperins [sic] interprètes de l’amour’. In the summer of 1936, Merry and Aubert returned to Versailles, giving concerts in the palace’s Salon de la paix, and in the Salon des jardins in the Grand Trianon. In December, they played together in an upmarket Paris showroom or gallery.

Thereafter, I’ve found nothing until April 1939, when Merry and Aubert were in The Hague, playing works by Blavet, Louis de Caix d’Hervelois, Jean-François Dandrieu, Louis Hotteterre (one of several musicians of this name), Rameau and Charles de Lusse. This was only the second trip I have traced which took Merry outside France before the War; the patchiness of periodical digitization and access means I’ve probably missed others.

Meanwhile, Merry had not abandoned the moderns. On 12 December 1935, he took part in the inaugural concert promoted by La Spirale, playing the Six petits préludes for flute and violin by Georges Migot, the group’s president. This served one of la Spirale’s aims, which was to privilege repeat performances over premieres, in its wider mission to promote contemporary music, French and foreign, in concert. On 5 March 1936, La Spirale put on an American programme, for which Merry and his former wife Elen Foster, alongside other Spirale members such as Olivier Messiaen, played works by Harrison Kerr, Roger Sessions, John Alden Carpenter, Wallingford Riegger, Isadore Freed, Charles Ives and Quincy Porter. Merry played Riegger’s Suite for flute alone, and revisited Porter’s Suite in E for flute, violin and viola, which he had premiered with Porter himself almost exactly five years before.

On 16 March 1937, Merry took part in the second concert promoted by another new group, La Jeune France. Founded the previous year, it’s now remembered mainly for its most famous member today, Messiaen, but it numbered another composer more important to Merry: André Jolivet (1905-1974), also a member of La Spirale. In 1936, Jolivet had composed Cinq Incantations for solo flute, and on 14 January 1937 Merry premiered some of them at La Sorbonne, reportedly because his peers were too conservative for such music. Later that month, he gave a second, private performance of some or all of the Incantations; and at the March concert of La Jeune France, Merry played three. Jolivet dedicated the cycle to Merry, whether before the premiere or in recognition of his advocacy I don’t know. Soon after composing the five Incantations, Jolivet wrote a free-standing Incantation pour que l’image devienne symbole, originally scored for solo violin (G string) or ondes Martenot, but premiered by Merry in 1937 on the flute (I have not identified the occasion); the violin premiere was not given until 1967.

In May 1938, at a salon concert organized by La Jeune France, Merry again presented three of the Incantations, as well as two pieces by another member of the group, Yves Baudrier (1906-1988), for which the flautist was joined by Elen Foster at the piano. The programme also included works by the British composers Alan Bush (1900-1995) and Alan Rawsthorne (1905-1971). Merry and Foster repeated the Baudrier items at another concert of La Jeune France later the same month. Intriguingly, in March 1939, at a concert held by La Jeune France in the salon of the duchess Edmée de la Rochefoucauld, Merry played the second of the Cinq Incantations while Foster executed a dance of her own devising.

The previous July, Merry and Foster had given the public premiere of a chamber cantata by Georges Migot, Vini vinoque amor (setting the composer’s own text), having premiered in private for the dedicatee. A year later, the partnership’s future must have seemed in doubt. At the outbreak of war, Merry and Foster travelled to his native Normandy, he to Cherbourg, to join an artillery regiment providing coastal defences, she to Caen to stay with Merry’s mother. It took Foster a year to escape. As the Burlington Free Press and Times of Burlington, Vermont, related in July 1941:

Mrs. Eleanor Foster Cohu of Claremont, N.H., a resident of France for 14 years before the invasion, was the guest speaker before the members of the Montpelier Rotary club Monday afternoon. Mrs. Cohu is an American girl and left Lisbon, Portugal, last Oct. 5 for the United States. She told of the first bombing on June 3, when the planes came down about noon, two bombs falling where she was staying, and two women being killed because they had wished to remain in their dining room, rather than seek shelter. She told of their laborious travel south […] to Pau, where they kept in hiding for six months. Mrs. Cohu spoke of the good work the American Friends society is doing in France, in Marseilles alone feeding between 30,000 and 40,000 school children each day. Everything this Quaker society collects, goes to France, she said.

After the Armistice, Jan Merry was presumably discharged and returned to occupied Paris. In February 1941, he played two of Jolivet’s Incantations at an public lecture by the composer. Later that year, Merry gave his first performance under the aegis of Le Triptyque, a concert series founded in 1934: on 5 July 1941, for a programme of Bach, Handel, Michel Corrette and others, Merry appeared with the tenor Paul Derenne (1907-1988) and the organist Marthe Bracquemond (1898-1973), who would later write a Sonatine for solo flute – whether for Merry, I don’t know (she had already written a work for him and Françoise Kempf to perform). In July 1942, he took part in a Triptyque concert of music by Arthur Honegger, with the soprano Noémie Pérugia (1903-1992).

Most important of all, on 7 May 1943, Le Triptyque devoted an entire concert to Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) with, again, Pérugia, a pianist and three wind soloists. Merry premiered two of the composer’s three Sonatines Op.184 for solo flute; he was also joined by his younger colleague Roger Bourdin (1923-1976), probably in the Sonata Op.75 for two flutes, and by the clarinettist Jacques Lancelot (1920-2009), possibly in the Divertissement Op.91. The concert marked the beginning of an important association, which would culminate in one of the monuments of solo flute music, and the subject of Dr. Arnone’s thesis: the ninety-six Chants de Nectaire, composed from April to August 1944 and named after a character in a novel by Anatole France. Merry premiered several of the Chants, some of which were dedicated to him by Koechlin (as is one of the Sonatines Op.184), and he continued to champion the Chants until the end of his career.

Which career, though? On that 1924 passenger list, Merry’s occupation was not given as musician – and he never became a professional flautist. For his entire working life, he was an electrical engineer, specialising in the lighting of halls, tunnels, streets and other public spaces. In this capacity, he was always known as Merry Cohu, which probably explains his slightly but distinctively different stage name (I wonder if he first used Jan in the US, to avoid any possible confusion with the female name Jean?). He seems to have qualified as an engineer in 1923, and he obtained a doctorate from the University of Caen with a thesis entitled Étude de quelques propriétés photométriques caractéristiques de certains verres diffusants à faces parallèles... [‘Study of some photometric properties characteristic of certain types of diffusing glass with parallel surfaces…’], published in 1932.

By 1935, Merry Cohu was Chief Engineer of the Research Group of France’s Society for the Improvement of Lighting, and by 1938 President of the lighting and heating chapter of the French Electrical Association. By 1959 he was General Secretary of France’s Committee for Lighting, and a consulting engineer to the leading Dutch electrical firm Philips. He spoke at conferences and symposia, and published extensively, from a 1924 article about light in a popular science magazine, to Récepteurs photoélectriques (École supérieure d'électricité / Malakoff, 1969). He translated at least one publication by a well-known physicist of gases, Frans Michel Penning (from Dutch, if you please).

Talking of publications, I’ve forgotten to mention that Merry edited four volumes of flute scales, studies and exercises by Giuseppe Gariboldi (1833-1905), and published his own transcription for flute and piano of Debussy’s Le petit nègre. There may be more. I don’t know if Merry ever had a teaching position – it seems unlikely, with his ‘day job’ – but he certainly had pupils, and he had a method. In fact, he was a formative influence on one of the most famous French flautists of the later twentieth century. As Dr. Arnone relates, remembering his kind schoolteacher in Normandy, Merry always

hoped to repay his “musical debt” to a talented and deserving pupil someday. That student would turn out to be his good friend’s son, Michel Debost.

Debost himself told a pupil of his,

In 1943, a friend of my father’s, Jan Merry, started me on the flute. He loved to play. His teaching was based on reading — first the original Altès Method, then duets of the Baroque, and many Mozart duets. I still think this reading skill is essential, because many technical hurdles in repertoire are just bad reading.

So, we’ve sort of reached the end of the War, when the paper trails I’ve been following run out. There are basically no hits on Gallica for Merry after the War – I don’t know why. Presumably Merry’s work as a consultant engineer took off, with so much infrastructure needing to be repaired, rebuilt and lit. But he was certainly still playing – according to Dr. Arnone, not just in France but also in Britain and Germany, and on one occasion he played one of Koechlin’s Chants de Nectaire

at an airport’s baggage claim in order to prove that his gold flute was indeed his property.

In December 1951, at a concert in Paris devoted to Koechlin’s works, the composer’s disciple Pierre Renaudin read the passage from Anatole France’s La révolte des anges which had inspired the Chants de Nectaire, after which Merry performed his own selection of five Chants. In her thesis, Dr. Arnone reproduces the programme of a concert given as late as August 1978, at which Merry played two Chants and one of Jolivet’s Incantations. Still, I would like to know more about Merry’s later life, including his work as an engineer. And it’s particularly irksome that I can’t find a notice of Merry’s second marriage, to a singer whose name I don’t know – possibly Magdeleine Camberlein. Their names are linked on a French genealogical site, but everything about his wife is hidden. One of the few details about Merry, rather sweetly, is his family nickname: ‘Tonton La Flûte’.

Anyway, it’s time we got down to hearing Merry’s records. I imagine Merry Cohu the engineer was less than impressed by Pathé’s slapdash production: not only is he billed differently on the two discs, the sides of the Handel sonata are mixed up. This label is stuck on what is actually the first side:

![Pathé PAT 37 [CPTX 163] label Pathé PAT 37 [CPTX 163] label](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0DFj2cAInE0jWotpduHuPihDTGWWoABhWIDMn3FiL-rbqwH34OasWWZA7dLW-vYg2eGanj89e5L1jEKLu2UPa5jLsqqnfnUcVrWrYW6Ipmf8Y38fiSPsw8u7t9TAR-Sx3O312d0viQ5XD/?imgmax=800)

This Pathé session was not, in fact, Merry’s debut on disc. He had been among the first artists to record for L’anthologie sonore (in September 1934, according to Michael Gray), the historical label master-minded by Curt Sachs (1881-1959), the musicologist and organologist, in exile from Nazi Germany. Blink, and you might miss his only known contribution: Merry is credited for just half of one side of L’anthologie sonore 3, playing in a 4-part lied by Heinrich Isaac (c.1450-1517) sung by the Swiss tenor Max Meili (1899-1970); the other item on the side didn’t require Merry. You can hear a good transfer by the Bibliothèque nationale de France on its Gallica site (note that the page mistakenly illustrates the label of the other side):

L’Anthologie sonore 3A

Isaac Zwischen Berg und Tal, Dufay Pourrai-je avoir

Max Meili (tenor), Jan Merry (flute),

Franz Siedersbeck (vielle), André Lafosse (trombone)

recorded September 1934

(date: A Classical Discography)

It’s possible that Merry performed in other L’Anthologie sonore recordings; not all instrumentalists were credited on labels. I doubt it, though: already on L’Anthologie sonore 9, a flute sonata by Blavet, a composer in Merry’s repertoire, was assigned to Marcel Moyse (1889-1984) – what’s more, with Pauline Aubert, who made many records for the series. Of course, Moyse was a great flautist and would have lent wider appeal to what perhaps seemed a label for specialists. But perhaps Merry’s sound was another issue: in that Isaac lied, notice how quick and almost febrile his vibrato is, more so than on the Pathé discs (but does the BnF transfer reproduce the recorded pitch?). His playing of these baroque items was not to the taste of the gramophone critic of the Paris paper L’Homme libre, one Nicolas Motais:

Une « Sonate » de Haendel (Pat. 37) et une « Suite » de Philidor (Pat. 36) sont jouées sans poésie et souvent sans justesse par le flûtiste Jan Merry.

[‘A Sonata by Handel (Pat. 37) and a Suite by Philidor (Pat. 36) are played without poetry, and often inaccurately, by the flautist Jan Merry.’]

I feel that’s harsh. Most reviews I’ve found of Merry’s Pathé discs are complimentary, though about the music rather than the performances (which was usual at the time, in reviews of records containing rare repertoire). Still, I must admit, what with the moments of off tuning and occasional scrambles, I don’t find Merry makes a particularly beautiful sound or lasting impression here.

But what in fact was Merry’s sound? That’s another reason this post has taken me so long. I’ve been itching to get blogging again, and especially to transfer some of my growing collection of 78s. Again, Jolyon and others have brought home to me the importance of transferring at correct pitch; but I don’t have a fully working varispeed turntable – only three which need attention… I chose these two Pathé discs, partly because I thought they’d be ‘easy’ to transfer, and partly because I wanted to listen to them to answer some discographical questions.

Oh dear – once again, little did I suspect… My copies are in goodish condition, and they responded well to light digital restoration. But when I played my transfers to a friend with perfect pitch, he wasn’t happy. So another friend kindly shifted the pitch, which didn’t entail a change large enough to cause artifacts, luckily. Now, my first friend was happy, but a flute historian I sent the shifted versions to, and whose opinion I very much respect, wasn’t. This all happened a year ago, and came on top of a sorry saga of me attempting to buy a varispeed turntable on ebay and being messed around by an ethically, socially and orthographically challenged seller, plus buying a second copy of one of Merry’s discs only to find I already had it.

So I’ve decided to stop messing about and upload the shifted transfers. Each disc has been transferred as a single sound file, in FLAC and Apple Lossless formats (feel the ecumenicity). Both discs are bundled together in one Zip file, which can be downloaded from here:

FLAC format

ALAC format

A few final things. There is one, just one, tantalising rerefence online to a commercial recording by Jan Merry of Koechlin’s Chants de Nectaire, supposedly issued on 5 LPs by the little-known French label Encyclopédie Sonore Hachette. That would be extraordinary, if true, because I’ve seen no mention of this possibly complete recording in any printed or online sources I have consulted (including an entire website devoted to the Chants). The only confirmation I can find is a listing of another Encyclopédie Sonore issue, containing a recording of Racine’s Phèdre, performed by a cast including Emmanuèle Riva, directed by the label’s founder, Georges Hacquard, and with ‘Flute music written by Charles Koechlin, performed by Jan Merry.’ Very much in a French tradition of incidental music for solo flute which goes back to Debussy’s Syrinx, Hacquard’s production, I would guess, draws on the above recording of the Chants. Having Merry’s recordings of Koechlin’s Chants would radically change our aural image of him: for all their interest, these Pathé discs are really Aubert’s affair, with Merry playing a slightly secondary role.

After the War, Eleanor Foster returned to Paris. For a time, she resumed her musical partnership with Merry. On 27 January 1947, they premiered Migot’s Sonate en cinq parties, dedicated to them. Migot also dedicated several pieces to Foster alone, from Le verseau [Aquarius], the first piece of his piano cycle Le Zodiaque, to two piano preludes, written as late as 1969-70. Meanwhile, Foster continued to reinvent herself. According to a 1975 newspaper interview quoted by Andrea Olmstead, ‘For 18 years she was the musical organiser and scriptwriter for a Masterworks of French Music radio program, heard on 300 American radio stations.’ So she was responsible for all those Masterworks of French Music LPs we see advertised for sale on the internet! (An example.) Foster also pursued another calling which she’d already explored before the war with Merry (see above):

A love of dancing and an investigation into a method of improving “centered coordination” led to a series of exercises she evolved that strengthened a belt of muscles in the solar plexus region. She wrote a book in French on the subject, The Solar Center of the Body: Source of Energy and Equilibrium. The interviewer noted that Eleanor was her own best advertisement: “At 78 she moves like 40; her enthusiasm glows like 20.”

Le centre solaire du corps was published in 1973. Above, the cover of a 1977 edition; it was reprinted well into the 1980s. I love Foster’s new moniker; finding it led me to her other publications:

-

Herzen, Monod; Forget, Maud; Foster, Ellé; Toupotte, Roland, et al. Médecine, parapsychologie et spiritualité, Éditions Martinsart, 1976

-

Foster, Ellé Mère la terre m’invite à danser: méthode d’éducation corporelle pour les enfants, Épi, 1979

It comes as something of a shock to read further in Olmstead: ‘The hearsay [...] is that Eleanor may have committed suicide.’

A bitter-sweet final note. In an e-mail to Dr. Arnone, quoted in her thesis, Michel Debost wrote:

Jan Merry was a prominent electrical engineer, but his only passion was for the flute. He had always wanted to be a professional flute player and regretted it to his dying day…

It’s a pity that his passion is so meagrely documented, but Dr. Arnone made a start in her thesis, and we’ve added a bit more detail.

ADDENDA

20 September 2017:

I’ve just come across the Netherlands’ superb digital portal Delpher, thanks to which I have details of some of Merry’s appearances in Holland.

The earliest currently documented in Delpher’s newspaper archive is an introduction to 18th century French music, given on 18 April 1939 to students of the Amsterdam Conservatoire, in the old building’s Bachzaal. It was presented by Pauline Aubert, who took the lion’s share of the programme, Merry joining her in pieces by Michel de la Barre and, possibly, Philidor. The following day, at the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague, the duo gave a longer public concert, again drawing on French baroque repertoire, which Aubert played on a harpsichord from the museum’s collection. No fewer than four Dutch papers reviewed the concert, not entirely favourably. Tempering the mostly positive verdicts on Merry’s playing were criticisms of his sound, intonation, and choice of apparently weak solo items by Hotteterre and Blavet.

Not until 1961 does Merry reappear in these digitized Dutch newspapers, again performing at The Hague’s Gemeentemuseum on 16 November; no details of the programme or other artists were reported. In February 1964, Merry gave his last concert documented in these sources, at Amsterdam’s Institut Français, also known as the Maison Descartes (recently sold). With the pianist Nicole Aubert (her relation to Pauline is unknown), Merry performed French music by the baroque composers Blavet, Leclair and Caix d’Hervelois, and, from his own time, Migot, Koechlin, Francis Poulenc and Jehan Alain. The only review I’ve located was damning, pronouncing the baroque first half ‘a disappointment’, and finding little more to commend in the ‘moderately modern’ pieces; only Poulenc’s Sonata won favour, as a piece and a performance.

Sources

Ancestry.com (genealogical, travel and other documents; subscription required)

Arnone, Francesca A Performance Edition of Kœchlin’s Chants de Nectaire Op.198 [DMA thesis], University of Miami, 2000

Clough, F.F. & Cuming, G.J. The World’s Encyclopaedia of Recorded Music, London: Sidgwick & Jackson & Decca Record Company, 1952, 1953, 1957

Councell-Vargas, Martha ‘Michel Debost: Teaching Artistry’, The Flutist Quarterly, Vol.XXXVII No.3, Spring 2012, pp.26-29

Delpher (Dutch newspapers, periodicals, books and other sources; open access)

Duchesneau, Michel L’avant-garde musicale et ses sociétés à Paris de 1871 à 1939, Mardaga, 1997

Gallica (French newspapers, periodicals and other sources, audio and image files; open access)

Gray, Michael A Classical Discography (open access)

Honegger, Marc [ed.] Catalogue des oeuvres musicales de Georges Migot, Les Amis de l’Œuvre et de la Pensée de Georges Migot / Association des Publications près les Universités de Strasbourg, 3e Série, Initiations et Méthodes, No.13, 1977

Jansson, Anders booklet note for Sforzando SFZ2001, 2000

Kayas, Lucie André Jolivet, Fayard, 2005

Meunier, Jean-Pierre La naissance de Malavoi [blog post], 1 August 2006

Nelson, Susan The Flute on Record: The 78 rpm Era, Scarecrow Press, 2006

Newspapers.com (mainly US newspapers; subscription required)

Orledge, Robert Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) His Life and Works, Harwood Academic Press, 1989

Powell, Ardal The Flute, Yale, 2003

Simeone, Nigel ‘La Spirale and La Jeune France: Group Identities’, Musical Times, Vol.143, No.1880 (Autumn 2002), pp.10-36

Wikipedia (open access)

Worldcat (bibliographical and discographical data; open access)

Acknowledgements

Dr. Heidi Álvarez

Dr. Francesca Arnone

Dominique Beaufils, Conservatoire de Caen

Martha Councell-Vargas

Dr. Abigail Dolan

Frans Hupjé, Philips Museum

Jolyon

Nigel Simeone

Jonathan Summers

![Pathé PAT 36 [CPTX 165] label Pathé PAT 36 [CPTX 165] label](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjFBdRRLcqs2jpwUEtKppy47MGTWuIUVhysun61snO1KwTrm23robe86dz3Jf2A0l_sHx66ofBYzI7a0c24E1gzEizJ4cxDyqnHM35_MgMM6TDzQjA5y2SQ09AJz2A0iFaHcABfnJ88aNPv/?imgmax=800)

![Pathé PAT 37 [CPTX 163] label Pathé PAT 37 [CPTX 163] label](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0DFj2cAInE0jWotpduHuPihDTGWWoABhWIDMn3FiL-rbqwH34OasWWZA7dLW-vYg2eGanj89e5L1jEKLu2UPa5jLsqqnfnUcVrWrYW6Ipmf8Y38fiSPsw8u7t9TAR-Sx3O312d0viQ5XD/?imgmax=800)

![Edison Bell VF 674 [X 1576] label 5DII 125, 12-Jul-15 Edison Bell VF 674 [X 1576] label 5DII 125, 12-Jul-15](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiFs6nb-D7LV3m2p3MHaPfMP-BZSdCUdgYom6SR6i7eDEFejOOCmDyBHEmLa8ejWxtiKp5KDiI-Dv9ji3JiFJwVsIYeB8vX5wq6J7m42eabNFvNkIUbUo5loyU8dxJCNXqZJyF0EF9bNIVX/?imgmax=800)