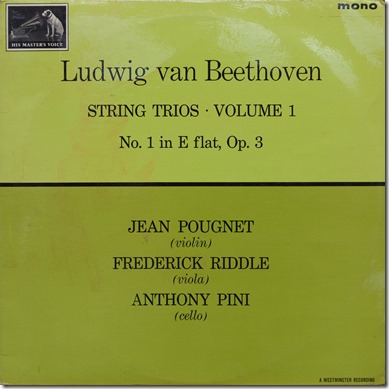

Beethoven String Trio in E flat Op.3

Jean Pougnet (violin)

Frederick Riddle (viola)

Anthony Pini (cello)

rec. 12 to 18 September 1952, Konzerthaus(?), Vienna

by Westminster (USA)

transfer from 1964 UK issue on HMV CLP 1765

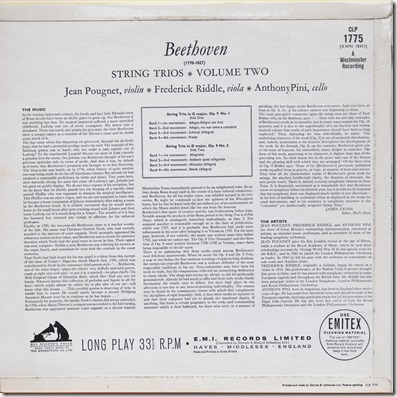

Beethoven String Trios in G Op.9 No.1 & D Op.9 No.2

Jean Pougnet (violin)

Frederick Riddle (viola)

Anthony Pini (cello)

rec. 12 to 18 September 1952, Konzerthaus(?), Vienna

by Westminster (USA)

transfer from 1964 UK issue on HMV CLP 1775

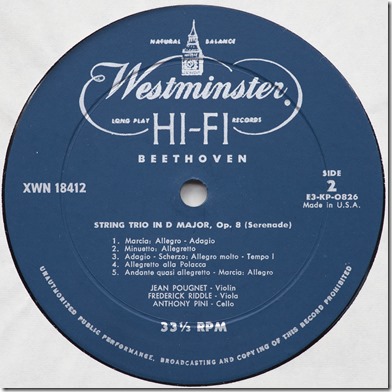

Beethoven String Trios in c minor Op.9 No.3

& in D Op.8 ‘Serenade’

Jean Pougnet (violin)

Frederick Riddle (viola)

Anthony Pini (cello)

rec. 12 to 18 September 1952, Konzerthaus(?), Vienna

by Westminster (USA)

transfer from 1964 UK issue on HMV CLP 1785

While I was at it, I thought I should share these other recordings by Pougnet, Riddle and Pini. I really enjoy these works, in which Beethoven is clearly flexing his muscles as a composer of weighty but playful and varied chamber music for strings – before tackling the biggie… And I love these recordings, as I do this group’s Divertimento K.563 of Mozart, which I shared in my last post, and which must have been a stimulus for Beethoven’s Op.3 and the model for Op.8.

Not much more to say, except to say that I feel Westminster’s excellent 1952 recordings (complete with… Viennese tram rumble?) have again come up well in these transfers from 1964 HMV issues. I wonder why EMI licensed them that latet?) They were only available for a very short time – deleted by the end of 1966 – so they’re not that common. I don’t think the first two LPs come from my late father’s collection – I must have got them second-hand. The third, I borrowed from a library, but I couldn’t then scan or photograph the sleeve; I’ve since acquired one of the Westminster issues, so I’ve included images of its sleeve and labels:

I didn’t photograph the HMV labels, as the inner sleeves have opaque paper liners (good choice!), and I don’t have a clean horizontal surface to photograph disc labels on (you do know the Cave is more of a tip than ever, don’t you? I’m losing my grip – no, make that: I’ve lost it…).

So, to download these LPs, as fully tagged mono FLACs plus images, in Zip files, follow these links:

There’s plenty of information about the works on the interwebs and in the sleeve notes which I’ve also included in the Zip files, such as this wonkily glued one:

A quick look at previous recordings of these still somewhat overlooked works:

Op.3:

no version on 78s

first recorded c.1951, Pasquier Trio, Allegro

Op.8:

first recorded 1934, Szymon Goldberg, Paul Hindemith & Emanuel Feuermann, Columbia UK, also issued in US & elsewhere

1936, Pasquier Trio, Pathé; issued in US and UK on Columbia

1950, Joseph & Lillian Fuchs, Leonard Rose, US Decca LP

1951, Erich Röhn, Reinhard Wolf, Arthur Troester, DGG, variable micrograde 78 + LP

c.1951(?), Trio à cordes de la Garde Républicaine, Saturne picture-disc 78

c.1951, Pasquier Trio, Allegro (with Op.9 No.1)

Op.9 No.1:

first recorded 1938, Pasquier Trio, Pathé; issued in US and UK on Columbia

c.1939?, Mara Sebriansky, Edward & George Neikrug, Musicraft

c.1951, Pasquier Trio, Allegro (with Op.8)

18 September 1952, Bel Arte Trio, US Decca LP (with Op.9 No.2)

Op.9 No.2:

first recorded 1949, Pasquier Trio, L’Anthologie Sonore 78 + LP

c.1951, Pasquier Trio, Allegro (with Op.9 No.3)

18 September 1952, Bel Arte Trio, US Decca LP (with Op.9 No.1)

Op.9 No.3:

first recorded March 1934, Trio de Bruxelles, Columbia France; also issued in UK

April 1934, Pasquier Trio, Pathé; issued in US and UK on Columbia

1950, Joseph, Lillian & Harry Fuchs, Decca US LP (with Joseph & Lillian Fuchs, Julius Baker, Serenade in D Op.25)

c.1951, Pasquier Trio, Allegro (with Op.9 No.2)

Let me know if I’ve missed any!